Solo Exhibition

Opening Date

Thursday / Kamis : 14 June 2007

Time/Pukul. 19.30 WIB

at Cemara 6 Galeri

1st Floor

Pengantar Kuratorial

CAMOUFLAGE (acts of war)

Oleh Rifky Effendy

“ Tapi di setiap zaman ada yang terbenam,ada yang tidak. Ada yang melawan”

Goenawan Mohammad, 1998

Hamad Khalaf dalam karya-karyanya menghubungkan Perang dengan Mitologi, yang berabad lamanya telah menjadi inspirasi bagi banyak kebudayaan manusia di dunia. Dalam dongeng-dongeng Yunani kuno, seperti dalam “Illiad”-nya Homer, tercermin bagaimana manusia saling membunuh, mencurangi satu sama lain, berkonspirasi dengan para dewa. Seolah perang adalah metafor dari nilai inti kehidupan sendiri. Pameran “ Camouflage : Acts of War”, menyentuh pokok soal perang dengan gestur yang lebih puitis dan erotis, tetapi juga politis. Menyamarkannya dengan apropriasi citra mitologi Yunani yang diterapkan kedalam obyek-obyek militer. Menyajikannya begitu rupa dalam rangkaian instalasi obyek- obyek, yang terbungkus rangkaian benda arkeologis, lazimnya dalam sebuah museum sejarah.

Hamad Khalaf dalam karya-karyanya menghubungkan Perang dengan Mitologi, yang berabad lamanya telah menjadi inspirasi bagi banyak kebudayaan manusia di dunia. Dalam dongeng-dongeng Yunani kuno, seperti dalam “Illiad”-nya Homer, tercermin bagaimana manusia saling membunuh, mencurangi satu sama lain, berkonspirasi dengan para dewa. Seolah perang adalah metafor dari nilai inti kehidupan sendiri. Pameran “ Camouflage : Acts of War”, menyentuh pokok soal perang dengan gestur yang lebih puitis dan erotis, tetapi juga politis. Menyamarkannya dengan apropriasi citra mitologi Yunani yang diterapkan kedalam obyek-obyek militer. Menyajikannya begitu rupa dalam rangkaian instalasi obyek- obyek, yang terbungkus rangkaian benda arkeologis, lazimnya dalam sebuah museum sejarah.

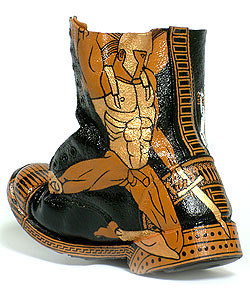

Masing-masing benda : masker gas, sepatu boot militer, replika helm tentara, replika serpihan-serpihan tembikar, dan lainnya, dihiasi dengan hiasan serta gambar-gambar figur Yunani Kuno. Sarat dengan gestur metafor, didominasi warna hitam dan merah, yang mengapropriasi nuansa artefak pecahan tembikar dari vas jaman Yunani kuno. Seperti pada Harpies & Phineus, ia menghias masker anti-gas dengan gambar manusia dewa bersayap. Beberapa bagian diisi motif – motif stilasi flora yang dikombinasi pola geometris. Atau sepatu tentara Irak berhiaskan citra ular naga, sarung tangan karet bergambar fragmen Hercules yang tengah bertarung melawan seekor ular. Hampir seluruhnya, apropriasi dilakukan dengan garapan artistik yang disesuaikan dengan bentuk benda tersebut, sebagai suatu keutuhan konsep estetik apropriasi mitologi.

Masing-masing benda : masker gas, sepatu boot militer, replika helm tentara, replika serpihan-serpihan tembikar, dan lainnya, dihiasi dengan hiasan serta gambar-gambar figur Yunani Kuno. Sarat dengan gestur metafor, didominasi warna hitam dan merah, yang mengapropriasi nuansa artefak pecahan tembikar dari vas jaman Yunani kuno. Seperti pada Harpies & Phineus, ia menghias masker anti-gas dengan gambar manusia dewa bersayap. Beberapa bagian diisi motif – motif stilasi flora yang dikombinasi pola geometris. Atau sepatu tentara Irak berhiaskan citra ular naga, sarung tangan karet bergambar fragmen Hercules yang tengah bertarung melawan seekor ular. Hampir seluruhnya, apropriasi dilakukan dengan garapan artistik yang disesuaikan dengan bentuk benda tersebut, sebagai suatu keutuhan konsep estetik apropriasi mitologi.

Pengamat akan menemukan citra fragmen-fragmen berbagai tokoh mitologi Yunani. Seperti sosok Patrokles, Achilles, Theseus, Minotaur, Nike, dan lainnya yang dianggap mempunyai simbol yang sejajar dengan realita politik yang terjadi di timur-tengah kontemporer. Seperti contohnya karya Jason and the Golden Fleece (2006), yang ditafsirkan dengan kesetiaan para prajurit Saddam Husein ketika diperintahkan mencaplok Kuwait yang kaya minyak. Mitologi, bagi Khalaf adalah jalan masuk memahami nilai-nilai kesejarahan tentang budaya perang, bahkan menemukan maknanya yang baru. Secara pendekatan konseptual, ia membuat mitos artifisial, untuk tujuan agar pengamat mempertanyakan mitos tersebut. Seperti dikatakan Roland Barthes (Myth Today: 1957), mitos adalah suatu sistem komunikasi , suatu speech. Dibangun dengan meta-bahasa dengan bahasa –rampokan atau curian, yang berfungsi untuk menaturalisasi sesuatu yang tidak natural, mendistorsi suatu pemaknaan. Semua berpotensi menjadi mitos. Senjata terbaik melawan suatu mitos adalah menciptakan mitos artifisial (artificial myth); “ Since myth robs languange of something, why not rob myth?”.

Maka appropriasi – dikatakan oleh Robert S. Nelson – seperti juga mitos, adalah suatu distorsi; bukan lawan atau negasi dari pada “ rakitan semiotik yang utama” (The prior semiotic assemblage). Bisa bermutasi; berubah tanda – tandanya (signs). Apropriasi seperti lelucon, kontekstual dan historikal, ia tak pernah stabil, berubah oleh kontek dan sejarah baru, menjadi tanda-tanda baru. Contohnya Minotaur yang merupakan sosok mahluk aneh yang termarjinalkan, dan dianggap “yang lain”, terpenjara , tanpa daya, dalam suatu labirin. Maknanya menjadi simbol yang bisa selaras dengan persoalan diskriminasi ras, gender, pengidap penyakit AIDS, agama, dan lain sebagainya, yang terjadi sekarang. Mitos – mitos juga mempunyai kandungan pesan yang berkaitan dengan kondisi sosial dan politik pada masanya. Khalaf, lewat kamuflase, sedang mempertanyakan dan menyingkap peradaban Yunani, yang selama ini dianggap jadi dasar peradaban Barat modern, peradaban rasional dan demokratis yang mengagungkan manusia.

Berkaitan dengan hal tersebut, secara politis, arkeologi seringkali digunakan bukti sebagai alasan sebuah bangsa / negara untuk mengusir, menduduki, menguasai atau menghancurkan bangsa / negara lainnya. Obyek-obyeknya menjadi contoh bagaimana mitos dan realitas, secara fisik saling mempengaruhi dan terkait satu sama lain. Secara menarik, pembacaan kembali terhadap mitologi Yunani, dan apropriasinya, ia muat dalam karya proyek harian fiktif “Narcissus Sporadicus”. Didalamnya, ia menuangkan penjelasan konsep dan pikiran tentang karya-karyanya, dengan tata letak dan headline teks yang menggelitik pembaca; ini merupakan aksi yang lebih nyata dari apropriasinya. Nelson disini melanjutkan lebih jauh, seperti juga yang dipahami Edward Said, bahwa dalam tiap apropriasi budaya ;“ there are those who act and those who act upon, and for those, and for those whose memories and cultural identities are manipulated by aesthetic, academic, or political appropriations, the consequences can be disquieting or painful”. Secara bersamaan, apropriasi membolehkan kegunaan obyek-obyek seni di masa lalu atau sekarang untuk mengafirmasikan kembali secara terbuka, tidak menutupinya.

Kekaryaan Khalaf selalu terkait antara sejarah dan peristiwa personal, serta konteks sosial dimana ia berasal, Kuwait dan Timur-Tengah. Setelah perang teluk antara Irak-Kuwait usai di tahun 1992-an, ia baru kembali dari Paris. Masa itulah, ia bekerja pada sebuah perusahaan untuk mengumpulkan ranjau – ranjau, yang berserakan di padang pasir, ditinggalkan oleh tentara Irak setelah kekalahannya. Kemudian ia mengumpulkan beberapa benda untuk pribadi, bahkan beberapa diantaranya adalah senjata berat yang diselundupkan. Saat itu menurut Khalaf, ia mengumpulkan kurang lebih 600 buah obyek militer. Sebagian masih disimpan di tempat tinggalnya di Kuwait. Sebagian ia bawa ke studionya di Bali. Dalam pameran ini beberapa obyek dibuat replikanya, seperti helm besi tentara Irak.

Sejenak ia belum menemukan gagasan artistik pada benda-benda tersebut, mungkin hanya menjadi semacam memorabilia, hingga suatu saat ia menemukan fungsi lain daripadanya. Benda-benda itu, baginya menjadi medium yang tepat untuk mempersoalkan peristiwa yang tengah terjadi disekitarnya. Ia memadukan dengan kesenangannya yang lain, ketika remaja adalah membaca buku – buku mitologi Yunani. Perang dalam sejarah peradaban memang merupakan keniscayaan yang selalu mengiringi hidup manusianya. Ironisnya perang memancarkan enerji artistik yang luar biasa, seperti juga tema-tema dalam karya- karya maestro seperti: Goya, Picasso hingga Kollwitz, maupun karya sastra dan filsafat. Maka perang secara langsung telah memaknai budaya manusia dari jaman ke jaman secara estetika.

Ketika ledakan bom mengguncang pulau Bali tahun 2003, ia menyempatkan pergi lokasi Sari Club ( ground zero ) untuk memunguti pecahan keramik yang tercecer. Kemudian pecahan itu diberi artikulasi yang baru; menjadi fragmen suatu drama dalam “Perang Troya”. Pecahan itu dihamparkan didalam kotak kaca. Disini ia ingin menunjukan bahwa rangkaian peristiwa terorisme yang terjadi di Indonesia , setidaknya pasca peristiwa 9/11, merupakan hanya suatu episode dari sebuah narasi yang besar, suatu “soft – target” , dengan mengorbankan ‘orang-orang yang lemah’. “Artefak” khalaf menjadi narasi yang terpenggal dan tercerai satu sama lain, sehingga rangkaian narasi itu tampak seperti sebuah puzzle. Maka lewat karya ini, ia memberi gambaran tentang hubungan yang rumit, dan lapisan-lapisan yang saling berkait dengan sebuah kejadian. Karena begitupun dengan sejarah, dimana musabab tak pernah terjadi dengan sendirinya sebagai kejadian yang kebetulan. Tetapi selalu terkait dengan peristiwa – peristiwa lain; sebelumnya atau secara paralel. Suatu kejadian yang simultan.

Dalam tesis Clash of Civilizations, Samuel Huntington mengemuka bahwa saat ini, setelah perang dingin (dan akhir dari Ideologi) muncul berbagai konflik dalam politik global, disebabkan oleh benturan-benturan budaya diantara bangsa-bangsa dan agama. Terutama antara peradaban Barat dan Islam. Alasan ini digunakan oleh Amerika Serikat dan sekutunya (pasca 9/11), sebagai retorika untuk menekan secara politis, dan menyerang dengan kekuatan militer negara-negara timur tengah atau Islam, seperti Afganistan dan Irak. Memerangi terorisme diseluruh dunia, termasuk di Indonesia. Hal ini juga, akhirnya memunculkan kebijakan-kebijakan politik lokal dan global, yang diskriminatif serta rasial.

Dalam tesis Clash of Civilizations, Samuel Huntington mengemuka bahwa saat ini, setelah perang dingin (dan akhir dari Ideologi) muncul berbagai konflik dalam politik global, disebabkan oleh benturan-benturan budaya diantara bangsa-bangsa dan agama. Terutama antara peradaban Barat dan Islam. Alasan ini digunakan oleh Amerika Serikat dan sekutunya (pasca 9/11), sebagai retorika untuk menekan secara politis, dan menyerang dengan kekuatan militer negara-negara timur tengah atau Islam, seperti Afganistan dan Irak. Memerangi terorisme diseluruh dunia, termasuk di Indonesia. Hal ini juga, akhirnya memunculkan kebijakan-kebijakan politik lokal dan global, yang diskriminatif serta rasial.

Lewat karya-karya Khalaf, tentunya pengamat diajak mengartikulasikan lebih jauh pada situasi politik global sekarang. Mempertanyakannya lewat kamuflase arkeologi. Disana ditunjukan bagaimana sejarah peradaban manusia memang penuh konflik yang didasari banyak faktor. Ekonomi, kekuasaan, agama, kolonialisme, maupun perbedaan – perbedaan budaya, ras, gender dan lainnya. Membuatnya seolah ada perbedaan atas pandangan dunia atau persepsi. Konflik global yang tengah terjadi bisa saja berakar pada nilai yang lama, hanya saja dengan wajah yang berbeda, dan situasi baru. Rupanya cita-cita humanitarian Barat tentang kesetaraan nilai manusia, masih menyisakan jalan yang begitu panjang. Bahkan sebaliknya, malah semakin banyak ketak-adilan ; menciptakan pemandangan yang ironis; memperpanjang konflik.

Lewat karya-karya Khalaf, tentunya pengamat diajak mengartikulasikan lebih jauh pada situasi politik global sekarang. Mempertanyakannya lewat kamuflase arkeologi. Disana ditunjukan bagaimana sejarah peradaban manusia memang penuh konflik yang didasari banyak faktor. Ekonomi, kekuasaan, agama, kolonialisme, maupun perbedaan – perbedaan budaya, ras, gender dan lainnya. Membuatnya seolah ada perbedaan atas pandangan dunia atau persepsi. Konflik global yang tengah terjadi bisa saja berakar pada nilai yang lama, hanya saja dengan wajah yang berbeda, dan situasi baru. Rupanya cita-cita humanitarian Barat tentang kesetaraan nilai manusia, masih menyisakan jalan yang begitu panjang. Bahkan sebaliknya, malah semakin banyak ketak-adilan ; menciptakan pemandangan yang ironis; memperpanjang konflik.

References:

1. Wawancara dengan Hamad Khalaf di Jakarta dan Bali, tahun 2006.

2. Supriyanto, Enin. Pengantar Kuratorial katalog Acts of War , Nadi Galeri, Jakarta 2006.

3. Konsep Hamad Khalaf dalam Proposalnya, 2006.

4. Beberapa bagian saya ambil dari artikel saya tentang pameran Hamad Khalaf, di Harian Nasional : Kompas.

5. Barthes, Roland. Myth Today. A Roland Barthes Reader. Edited by Susan Sontag. Vintage. 1993. London. Hal. 123.

6. Nelson, Robert S. Critical Terms For Art History.The University of Chicago Press. USA. 2003. p. 163 – 164.

7. Ringkasan tesis ini di: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clash_of_Civilizations

english

Camouflage: Acts of War

“In each historical period, there are people who are muted, and those who are not. They are those who fight (Goenawan Mohamad 1998).

Hamad Khalaf’s exhibition, “Camouflage: Acts of War” connects War and Mythology. In the stories of ancient Greece , such as Homer’s Iliad, soldiers, kings and ordinary mortals are shown killing and deceiving one another. They are also shown engaging in plots with or against the gods. As if war were at the very heart of the human experience. The exhibition “Camouflage : Acts of War” similarly touches on the issue of war. Part of it is erotic in a poetical way, but the underlying message is mainly political. The exhibition consists of military object on which are painted scenes from Greek mythology. The presentation is made in such as way as to look like a display of archeological items in a Museum.

The items on which the mythological scenes are painted include gas masks, army boots, helmets, decanters, chemical attack gloves etc. All are painted in black and red, to suit their metaphorical function and look as real earthenware objects from Ancient Greece. For example the story of Harpies & Phineus appears as winged monsters “Tormenting Phineus” (2006) painted on a gas mask. Ornamentation, by floral and geometric motifs, is added to emulate the style of ancient Greek vases. Another famous story illustrated in a similar manner is that of “Hercules” (2006) fighting the serpent headed Hydra & visiting the garden of the Hesperides. The scenes are painted on a pair of protective gloves. The 9 snakes which make up the Hydra’s head are wrapped around the fingers of the left glove. Similarly, the branches of the golden apple trees are also wrapped around the fingers of the right glove. On an Iraki army boot entitled “Jason and the Dragon” (2006), the artist combines figures and ornamentation in order to create a 3 dimensional object, which is painted like an ancient Greek vase and yet has the shape of a worn-out army boot. What characterizes all those works is an artistic appropriation of mythology – the purpose of which will be discussed below. Among the most famous mythological characters thus appropriated, one recognizes the figures of Patrocles, Achilles, Theseus, the Minotaur and Nike, who all appear as metaphors for one aspect or the other of the contemporary political reality of the Middle-East. For example, the work “Jason and the Golden Fleece” (2006) refers to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of oil-rich Kuwait in 1990.

Khalaf uses and reinterprets mythology as a means to openly challenge the “culture of war”. He lays bare myths, so as to have us raise questions. Isn’t mythology, as explained by Roland Barthes (Myth Today: 1957), a system of communication, a discourse? Isn’t it a meta-language that uses “stolen” elements of language to render natural something that previously wasn’t, in other words to distort interpretation. Everything can become myth, and the best weapon to counter a myth is to create an artificial myth: “Since myth robs language of something, why not rob myth?”

Like the original myth, appropriation, says Robert Nelson, is a distortion. It can mutate and adopt new signs. Appropriation is like a joke; it has to be related to a context. By essence unstable, it creates ever new signs with every new historical context. An example of the phenomenon is given by the Minotaur myth, that of a strange and marginalized creature which is constructed as “the other” and therefore imprisoned, powerless, in a labyrinth. He becomes to Khalaf a symbol for all modern forms of discrimination. Broadening his interpretation, Khalaf also raises questions, via ancient Greece , about the present state of modern Western culture. He raises in particular the question of the factual validity of its paradigm of rationality and democracy developed around the notion of Man.

Archeology is often used as a tool of national claims whenever a nation looks for pretexts to occupy, dominate and eventually expel or even eradicate another nation. Archeological items then become the loci in which myth and reality interfere with one another. In his project named “Narcissus Sporadicus” (a spoof newspaper published in Hades), Khalaf uses archeological items for the purpose of such a re-reading of history. He also clearly explains, with well-designed captions for each item, the concepts that underlay his work, thus inducing the reader to react. Commenting on this appropriation, Nelson, referring to Edward Said, says that “there are those who act and those who act upon, and for those whose memories and cultural identities are manipulated by aesthetic, academic or political appropriations, the consequences can be disquieting or painful.” Appropriation authorizes the use of artistic items from past and present and exposes their true meaning.

Khalaf’s work is a discourse on war, involving both elements of history and of the artist’s personal life as well as places of origin – Kuwait and the Middle-East. When the first Gulf War came to an end in 1991, Khalaf, who was then in Paris , returned to his country. He found employment with a company contracted to clear the landmines scattered all over the battlefields and abandoned by the Irakis after their defeat. He used this position to constitute a collection of more over 600 war items. Some of which are now in his parents’ house in Kuwait . Others he later took to Bali , where his studio is now located. In the exhibition, some of the items used are duplicates, like the iron helmets of the German WWII soldiers.

At first, he simply considered the items in his possession as elements of a memorabilia. Only later did he find them a new function: being a medium to question events that had happened and so disturbed his life. He had loved Greek mythology since childhood. So he came up with the idea to combine Greek mythology with a statement against war. War is ever present in the history of human civilization. Pro and contra, it also engenders an extraordinary artistic energy, such as seen for example in the works of masters such as Goya, Picasso, Kollwitz, and in the numerous masterpieces of literature and philosophy that are dealing with it. War has colored Man’s culture throughout the whole range of history.

When bombs shook Bali in 2002, Khalaf managed to go to “Ground Zero”, the location of the former Sari Club, where he picked up scattered shards of ceramics left over from the explosion. He then gave those shards a new meaning; they became elements of a “Rubble Puzzle” associated with the Troyan War in the Iliad – opposing Greeks and Trojans. Those shards are presented in a glass top table. Here Khalaf shows that the series of terrorist events that have happened in Indonesia since the 9/11 World Trade Center attack, are part of a bigger narrative that eventually victimizes the weak. Khalaf’s artifacts become a narrative of scattered elements, and in the end his narrative appears like a puzzle – such as is the multi-complexity of the related chain of events set in motion by 9/11. In history indeed, events are never isolated. They are always related to other, parallel or previous, events.

In his book “Clash of Civilization”, Samuel Huntington says the Cold War will be followed by global conflicts between civilizations and religions. Especially between Western and Moslem civilization. This theory is now used by the United States and its Allies (post 9/11) as a pretext to political pressure, and sometimes attack with military force, Middle-East and/or Islamic countries such as Afghanistan and Irak. As well as to confront terrorism in the whole world, including in Indonesia . This reaction of the United States impacts on both local and global decision making processes. It also breeds religious and racial discrimination.

Khalaf’s works invites the observer to pay more attention and react to today’s global politics. He himself questions it through archeology. We are shown how the history of human civilization is full of conflicts – related to economics, power, religion, colonialism, as well as to cultural, racial, gender and other differences. Those global conflicts are sometimes rooted in old values, sometimes in new ones – or under a new guise. It seems that the Western humanitarian paradigm about human equality has still a long way to go (before it can be implemented). It even seems that injustice is growing. Ironically the humanistic paradigm advocated by the West seems to generate its opposite, ever new conflicts.

Biodata

Hamad Khalaf (Kuwait)

Born 1971

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2008 “Acts of War”. Gaya Fusion Artspace , Bali, Indonesia.

2007 “Acts of War”. 24hr Art (N.T. Centre for Contemporary Art). Darwin, Australia.

“Camouflage: Acts of War”. Galeri Cemara 6 , Jakarta. Rumah Seni Yaitu, Semarang.

“Acts of War”. Galeri Soemardja -ITB , Bandung, Indonesia.

2006 “Acts of War”. Curated by Enin Supriyanto. Nadi Gallery. Jakarta,

Indonesia.

2005 “Acts of War”. Curated by Filippo Sciascia. Gayafusion. Bali, Indonesia.

2001 “The Fires of Kuwait”.The green Room, Ritz Carlton Hotel. Singapore.

1999 “Enemy Revisited”. Salle des Pas Perdus, UNESCO Headquarters.

Paris, France.

1998 “Les Argonauts”. Hall Moro III, UNESCO Headquarters. Paris, France.

1997 “Enemy Revisited”. Musee de Louvain La Neuve. LLN, Belgium.

“Enemy Revisited”. Galerie Catrin Alting. Antwerp, Belgium.

1996 “Mitologia Crudele”. Loggia Rucellai – Galerie Alberto Bruschi.

Florence, Italy.

1995 “Enemy Revisited”. Le Centre Culturel Francais. Kuwait.

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2007 “Appropriation”. Curated by Rifky Effendy. Galeri Semarang. Semarang, Indonesia.

“Fetish”. Curated by Enin Suprianto. Biasa Gallery. Bali, Indonesia.

2006 “Theertha Open Day”. Organized by Theertha IAC. Hantane, Sri Lanka.

“Gaya Collection”. Gayafusion. Bali, Indonesia.

2005 “3 Regards sur la guerre”. Abbaye de Stavelot. Stavelot, Belgium.

“Pra Biennale”. Sika Gallery. Bali, Indonesia.

“Bali Biennale-Summit Event”. Komaneka gallery. Bali, Indonesia.

2004 “Artiade – Olympics of Visual Arts”. Athens, Greece.

1996 “Artiade – Olympics of Visual Arts”. Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

PROJECTS/ASSIGNMENTS/WORKSHOPS

2006 Theertha International Artists Workshop. Hantane, Sri Lanka.

2005 Created 40 art masks for sale at charity masquerade. “Friends of

Indonesia. Fabio’s. Bali, Indonesia.

2004 Member of the international Jury. Artiade Olympics of Visual Arts”.

Athens, Greece.

1998 Desk Caendar. Mobile Telecommunications company (MTC). Kuwait.

1997 Cards and “Minotaur” Watch sold at UNESCO HQ. Paris, France.

COLLECTIONS

Nadi gallery. Jakarta, Indonesia.

Gayafusion. Bali, Indonesia.

Musee de Louvain La Neuve. LLN, Belgium.

Maison de L’UNESCO. Paris, France.

Associasion Internationale des Arts Plastiques (AIAP). Paris, France.

Artiade Foundation (NGO). Berlin, Germany.

Professor Nicholas Saunders. Author of Trench Art books.

Miuccia Prada. Fashion designer and co-founder of the Prada Foundation. Milan, italy.

STUDIES & DAY JOBS

2001-2003 Senior Representative, Kuwait Petroleum Far East, Singapore.